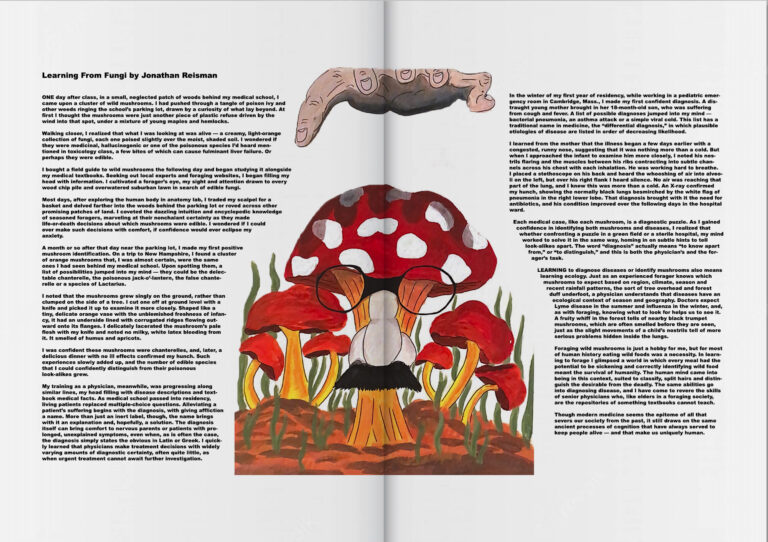

17 May Editorial Illustration

Emily Carr: Illustration – Editorial Assignment – Gouache on cold press paper

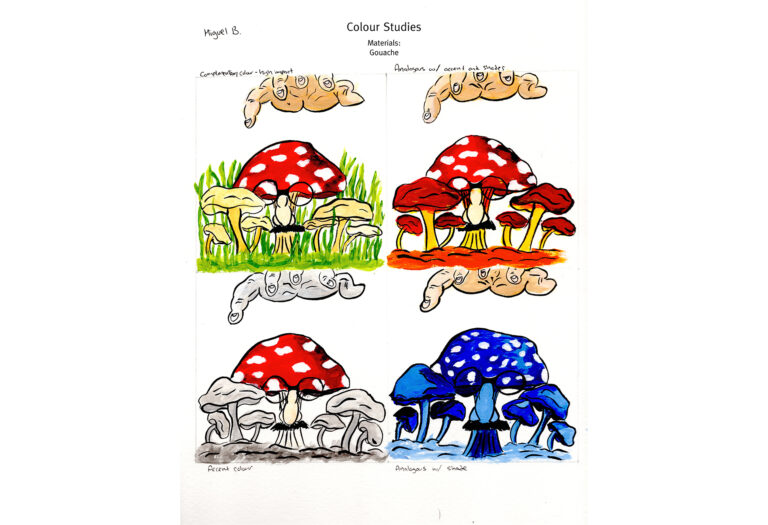

The task was to create an illustration using gouache that complemented the article by Jonathan Reisman, which you can find below. It’s written like a scholarly article speaking on the parallels between picking mushrooms in nature and diagnosing patients as a doctor. As an artist, I like going against the grain so for this illustration I focused on contrast and vintage-age-specific humour when delivering an illustration for this scientific article. To accomplish this I had my subject be an obvious poisonous mushroom that was disguised in order for the mushroom picker to incorrectly pick them. The poisonous mushroom would be among other edible mushrooms that looked almost identical except for some alarming differences, which could parallel with symptoms for different similar diseases/colds. It adds a bit of light-hearted humour for an article that is already pretty straight-arrow and serious.

Check out the article below:

Learning From Fungi by Jonathan Reisman

ONE day after class, in a small, neglected patch of woods behind my medical school, I came upon a cluster of wild mushrooms. I had pushed through a tangle of poison ivy and other weeds ringing the school’s parking lot, drawn by a curiosity of what lay beyond. At first I thought the mushrooms were just another piece of plastic refuse driven by the wind into that spot, under a mixture of young maples and hemlocks.

Walking closer, I realized that what I was looking at was alive — a creamy, light-orange collection of fungi, each one poised slightly over the moist, shaded soil. I wondered if they were medicinal, hallucinogenic or one of the poisonous species I’d heard mentioned in toxicology class, a few bites of which can cause fulminant liver failure. Or perhaps they were edible.

I bought a field guide to wild mushrooms the following day and began studying it alongside my medical textbooks. Seeking out local experts and foraging websites, I began filling my head with information. I cultivated a forager’s eye, my sight and attention drawn to every wood chip pile and overwatered suburban lawn in search of edible fungi.

Most days, after exploring the human body in anatomy lab, I traded my scalpel for a basket and delved farther into the woods behind the parking lot or roved across other promising patches of land. I coveted the dazzling intuition and encyclopedic knowledge of seasoned foragers, marveling at their nonchalant certainty as they made life-or-death decisions about which mushrooms were edible. I wondered if I could ever make such decisions with comfort, if confidence would ever eclipse my anxiety.

A month or so after that day near the parking lot, I made my first positive mushroom identification. On a trip to New Hampshire, I found a cluster of orange mushrooms that, I was almost certain, were the same ones I had seen behind my medical school. Upon spotting them, a list of possibilities jumped into my mind — they could be the delectable chanterelle, the poisonous jack-o’-lantern, the false chanterelle or a species of Lactarius.

I noted that the mushrooms grew singly on the ground, rather than clumped on the side of a tree. I cut one off at ground level with a knife and picked it up to examine it more closely. Shaped like a tiny, delicate orange vase with the unblemished freshness of infancy, it had an underside lined with corrugated ridges flowing outward onto its flanges. I delicately lacerated the mushroom’s pale flesh with my knife and noted no milky, white latex bleeding from it. It smelled of humus and apricots.

I was confident these mushrooms were chanterelles, and, later, a delicious dinner with no ill effects confirmed my hunch. Such experiences slowly added up, and the number of edible species that I could confidently distinguish from their poisonous look-alikes grew.

My training as a physician, meanwhile, was progressing along similar lines, my head filling with disease descriptions and textbook medical facts. As medical school passed into residency, living patients replaced multiple-choice questions. Alleviating a patient’s suffering begins with the diagnosis, with giving affliction a name. More than just an inert label, though, the name brings with it an explanation and, hopefully, a solution. The diagnosis itself can bring comfort to nervous parents or patients with prolonged, unexplained symptoms, even when, as is often the case, the diagnosis simply states the obvious in Latin or Greek. I quickly learned that physicians make treatment decisions with widely varying amounts of diagnostic certainty, often quite little, as when urgent treatment cannot await further investigation.

In the winter of my first year of residency, while working in a pediatric emergency room in Cambridge, Mass., I made my first confident diagnosis. A distraught young mother brought in her 18-month-old son, who was suffering from cough and fever. A list of possible diagnoses jumped into my mind — bacterial pneumonia, an asthma attack or a simple viral cold. This list has a traditional name in medicine, the “differential diagnosis,” in which plausible etiologies of disease are listed in order of decreasing likelihood.

I learned from the mother that the illness began a few days earlier with a congested, runny nose, suggesting that it was nothing more than a cold. But when I approached the infant to examine him more closely, I noted his nostrils flaring and the muscles between his ribs contracting into subtle channels across his chest with each inhalation. He was working hard to breathe.

I placed a stethoscope on his back and heard the whooshing of air into alveoli on the left, but over his right flank I heard silence. No air was reaching that part of the lung, and I knew this was more than a cold. An X-ray confirmed my hunch, showing the normally black lungs besmirched by the white flag of pneumonia in the right lower lobe. That diagnosis brought with it the need for antibiotics, and his condition improved over the following days in the hospital ward.

Each medical case, like each mushroom, is a diagnostic puzzle. As I gained confidence in identifying both mushrooms and diseases, I realized that whether confronting a puzzle in a green field or a sterile hospital, my mind worked to solve it in the same way, homing in on subtle hints to tell look-alikes apart. The word “diagnosis” actually means “to know apart from,” or “to distinguish,” and this is both the physician’s and the forager’s task.

LEARNING to diagnose diseases or identify mushrooms also means learning ecology. Just as an experienced forager knows which mushrooms to expect based on region, climate, season and recent rainfall patterns, the sort of tree overhead and forest duff underfoot, a physician understands that diseases have an ecological context of season and geography. Doctors expect Lyme disease in the summer and influenza in the winter, and, as with foraging, knowing what to look for helps us to see it. A fruity whiff in the forest tells of nearby black trumpet mushrooms, which are often smelled before they are seen, just as the slight movements of a child’s nostrils tell of more serious problems hidden inside the lungs.

Foraging wild mushrooms is just a hobby for me, but for most of human history eating wild foods was a necessity. In learning to forage I glimpsed a world in which every meal had the potential to be sickening and correctly identifying wild food meant the survival of humanity. The human mind came into being in this context, suited to classify, split hairs and distinguish the desirable from the deadly. The same abilities go into diagnosing disease, and I have come to revere the skills of senior physicians who, like elders in a foraging society, are the repositories of something textbooks cannot teach.

Though modern medicine seems the epitome of all that severs our society from the past, it still draws on the same ancient processes of cognition that have always served to keep people alive — and that make us uniquely human.